America on Hospice

Imagine you have a sick relative that, despite a problematic past, you have fond memories of. They were always nice to you. They might have given you cookies when your parents weren’t looking, or put money in your pocket on your way out the door. And they were funny! They were so quick with a joke and always made you laugh. When you were young, you didn’t notice how the jokes or comments might be insensitive. But once you got older, it became apparent that this kindly old relative, while always nice to you, had some really problematic views. Some further research into your relative’s past uncovered even more glaring concerns. It turns out that social club they were always talking about were racists with a history of violence. This is not the pleasant family member you fondly remember. Or at least, that’s no longer the whole picture.

And now, this realtive has become quite ill. Their passing has become all but inevitable. Given everything you know now, you don’t want to visit them. You barely even want to grieve their eventual demise. But there’s still a part of you, a connection with the child you used to be, that remembers the kinldy old relative and will mourn them. It’s also impossible to determine how the death of this relative will impact the rest of the family. For better or worse, this relative has been an important part in keeping the family together. What will happen to the rest of us when they’re gone?

This heavy-handed anlogy represents the United States of America.

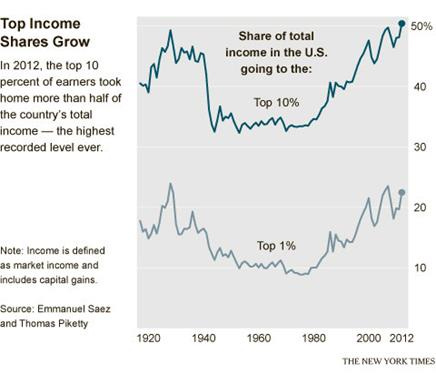

Both sides of the political isle seem to agree on one thing: America is sick. And while they agree on precious little else, they do seem to agree that the gulf between the elites and the regular folks is widening. This, at least, is prety apparent. We are experiencing levels of wealth-income inequality not seen since the first Gilded Age, leading some to declare that we are in a Second Gilded Age currently.

Unfortunately, it’s here that the agreement ends. What qualifies someone as an elite is a debateable point. And whether or not those elites deserve their position in the heirarchy is, too. Both sides, however, seem to be very concerned about defining those terms. To conservatives and the wider political right, the “woke mind virus” is what’s keeping average American from realizing their potential. Whether this is caused by Cancel Culture, immigration, DEI, or a new villian of the week, they will claim that the game has been rigged against the regular people. While this does nothing to explain the reality that Americans face, it does give them an easy boogeyman to focus their efforts against. For those on the right, those with a “righful” place in social ladder are being displaced because of efforts towards inclusivity.

For liberals and leftists, there is similar discussion about whether elites deserve their positions. For them, nepotism and systemic racism have put undeserving people at the top of the pyramid. Liberals might want to keep the current system in place while adjusting the parameters for fairness, beliving that tinkering along the edges will bring the equality we’ve been promised. Leftists largley belive the system to be the cause of problem and would rathter have a something new to replace the old. The remarkable thing about all of these stances is the acknowledgement that what we’re doing is not working.

Much has been made about the average life expectancy of an empire being 250 years, being that America is on the cusp of its 250th anniversary. Whether or not there’s any merrit to this claim is irrelevant. Whether or not America could be defined as an empire (I’d say it is) or whether an average empire actually lasts 250 years (who’s to say when an empire offically begins or ends?), America is closer to the end of its life expectancy than the beginning.

So how long do we have? What a good looking question! Once we made the decision to stop conventional care and move into hospice, my own father lasted only a few days (he didn’t want to hang around any longer than he had to). I’ve certainly heard and read about people that linger for months on end-of-life care (sometimes due to fraud on the part of insurance companies). For reasons not entirely within the control of stakeholders within the US, we probably won’t get to hang around for an extended period. The harbingers of climate change, geopolitical instability, and global economic conditions, will have a lot to say about it; mixed with our accelerationist electoral tendencies. Regardless, the order of business is the same as the elderly yet problematic realtive we discussed earlier: We mourn what was, while acknowledging the flaws, and prepare for what comes after.