Complexity - Diversity = Fragility

Complex Systems and Co-evolution

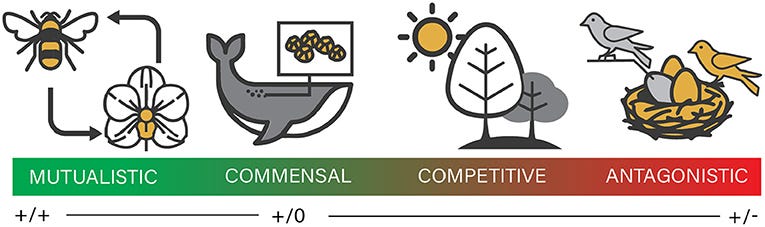

Along with the idea of “survival of the fittest” that many associate with Charles Darwin, he also wrote about the co-evolution of species. Organisms don’t just compete for resources and get better through competition. They also evolve alongside other organisms in multiple different ways. Sometimes this is a predator-prey relationship, sometimes it’s a mutual relationship, and other times species will fill similar ecological niches in different ways. Terrestrial ecologist and forestry professor Tom Wessels has a great YouTube video on this that I can’t recommend enough (if you’re into that sort of thing). One example of co-evolution discussed is that multiple organisms might fill a very similar ecological niche, but do so at different times throughout, at different elevations of the forest, or with different subspecies of trees, etc. This means that if the population of one organism starts to collapse, another is available to expand its ecological zone, or change the time of day they are active, and help that biological process continue. Granted, this change occurs over generations. But in geological terms that’s still pretty fast. This built-in redundancy caused by the diversity of species through co-evolution makes the system more resilient to change.

While listening to a recent episode of the Breaking Down: Collapse podcast, the host was discussing what could happen when the complex systems that make up our civilization start to fail. We in the Imperial Core (i.e. - the predominantly Western “developed” nations) benefit greatly from these complex systems. We get consumer electronics from China, out-of-season produce from Mexico, and travel around the world with an ease never seen before. And if those in the “collapse aware” community are correct, we may never see it again. Whether perceived as happening all at once or a rolling snowball shitshow that journalist Robert Evans refers to as “The Crumbles,” there is likely a point on the horizon where this golden goose we’ve been benefiting from stops laying eggs.

Our civilization is built on a complex interconnected system of smaller subsystems, and each one is integral in making the whole function properly. We’ve already seen what disruptions of various sizes can do to the global supply system. A cargo ship stuck in the Suez Canal blocked hundreds of ships from passing through and caused hundreds of millions in economic losses. Scaling up to the COVID pandemic, it’s estimated that it cost the world over $11 TRILLION and counting. No doubt you felt both of these somehow as increased prices and longer wait times were common. So what happens if instead of an interruption, one or more of these systems just stops? What comes in to take the place of the failed part of the system?

In a balanced ecosystem with healthy diversity, one part of the system stopping should cause other parts to compensate eventually. If one individual species collapses due to disease or loss of its normal food source, another population should increase over time to ensure the ecosystem continues to run effectively. This is what can make invasive species so dangerous to an ecosystem: something from outside the ecosystem coming in and throwing it out of balance. Whether the source of pressure is internal or external, the system should eventually find balance. The alternative is total collapse of the ecosystem.

I believe there’s a lot of overlap between the interconnectedness and complexity of the global economy and an ecosystem. That being the case, I don’t feel like complexity is the problem. Complex systems can be incredibly resilient. The issue arises when a complex system lacks the diversity to adapt to change. When there isn’t another adjacent species to take the place of one when if it fails, the entire system suffers. Our economy functions in much the same way. Had the Suez Canal been destroyed instead of only being temporarily blocked, the economy would have never been the same.

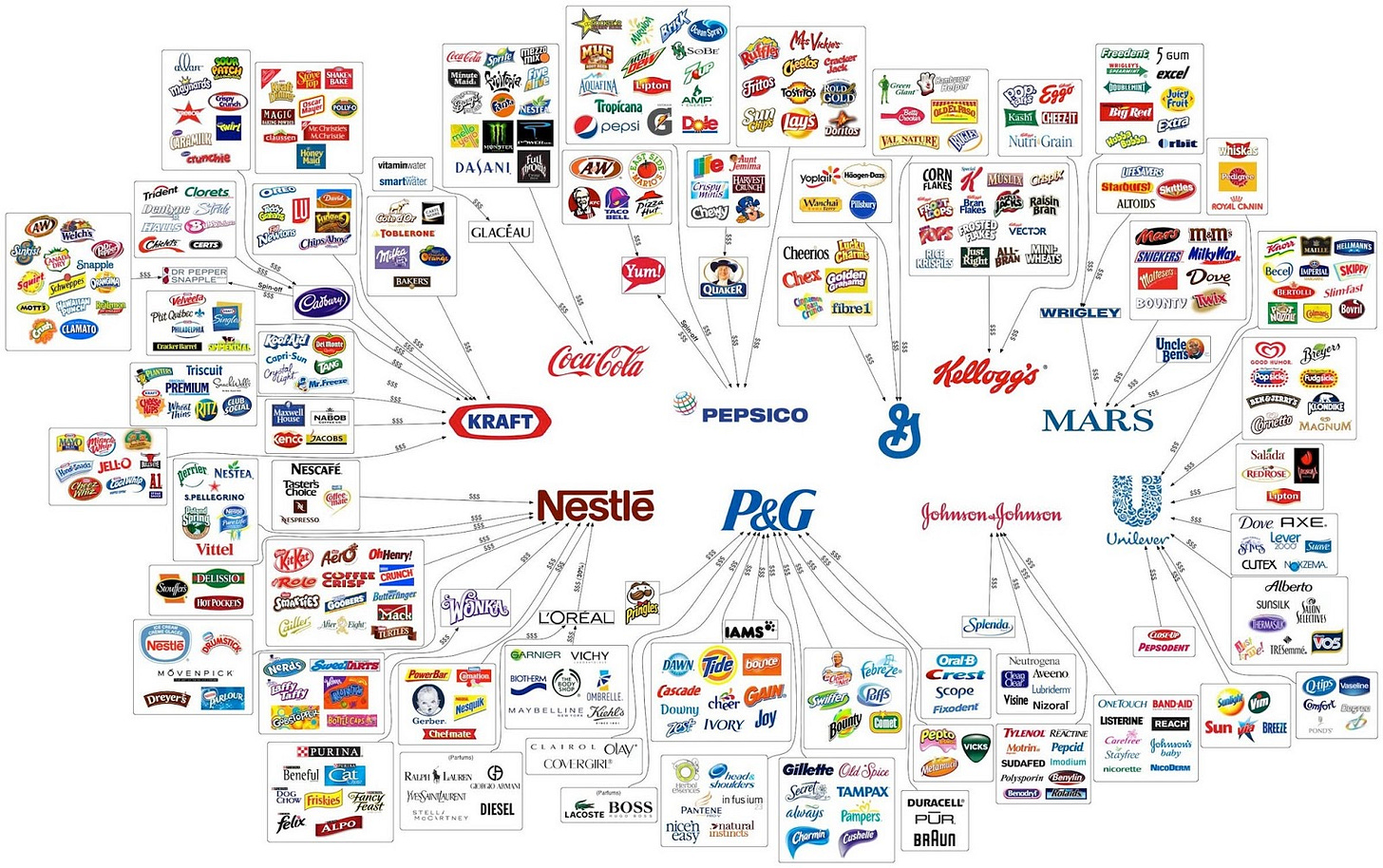

By design, our economy has a built in invasive species: capitalism. Many like to say that competition is the key to capitalism, but this simply isn’t the case. Competition is an essential component to markets, which is not saying the same thing. Markets have been around since humans had the ability to barter, but capitalism has been around since around the 1700s (depending on your source). A company would be plenty content to be a monopoly. They would love to be the only supplier of a product or service. They would then control how much materials and labor cost, and how much they can charge consumers. Antitrust laws that seek to break up monopolies or keep them from forming are our way of keeping this invasive species in check. If we didn’t do this, not only would it be bad for the consumer, but the loss of that single supplier would be catastrophic for the rest of the economy and could seriously impact society.

While some monopolies are present in our system, many others are oligopolies; there are few providers for a product. For example, it may seem like there are nearly limitless choices when it comes to buying food in the United States, the reality is that you are most likely buying from one of ten major companies. The market says more options are good for consumers so they can get the best price for a product. The added benefit of competitors in a market is that it adds resilience. If one provider fails, others fill the void. Each time one of the bigger companies bought a smaller competitor, this was capitalism at work undermining the market. By concentrating wealth in fewer hands, less options were made available and more fragility was introduced into the system. Think of what would happen if it were only one company controlling the entire food market in the United States. They could set their own prices and pay as little as they wanted for labor and materials. Worse yet, consider what happens if that company failed or decided to withhold goods. Where else could you go for food in that case? Unless you’ve got a good farmer’s market nearby, you could be in serious trouble.

In engineering terms, many people might have heard the term “single point of failure.” This is meant not to indicate that, “We finally got rid of all the needless redundancy and are truly efficient!” Instead, this says, “Everything is riding on this one component, and if it fails the whole thing comes apart.” Redundancy is not efficient. Keeping parts on hand to make repairs is not efficient (from a financial perspective anyway). However, these things add resilience to the system. They make it so the failure of a single component does not take down the whole system, much like biological diversity in an ecosystem or diversity of providers in a market.

Complexity on its own is not bad, but we should not be trusting the complex systems we’ve built to fewer and fewer people. Even if you assume that the complex systems of our economy were only put in place because of capitalism (which I don’t think is necessarily true), that doesn’t mean we should take the guard rails off. We should be leery of anyone that wants to turn their social media platform into an “everything app” that covers multiple aspects of your life and has no real competitors. We should be aware that every attempt to remove redundancy from the the parts of government many of us depend on will result in increased fragility of that system and make it more prone to breakdown. Efforts to end diversity programs in the workforce are yet another attempt to concentrate the mechanisms of power into fewer hands, which will make the system more fragile. This headlong dive into efficiency — first seen in the corporate sector and now being applied in the most cold blooded way possible to the US government — is going to make the system less stable, less able to provide essential services, and more prone to failure. If we don’t want to go through a series of forced simplifications of our systems, which some would use as the definition of collapse, the answer is to put that complexity into more hands, not fewer.